Blossoms against the machine

“Come to me, said the world,"

(Louise Glück, from “October,”)

“Computer says, ‘no’,"

(David Walliams in “Little Britain”)

In Tasmania, contrast makes plain the root of the crisis. Wild forest is patched by plantations. Uniform neat rows of adolescent blue gums on bare ground, or the howl of a clearfell, are broken by unruly tracts where old trees senesce alongside saplings. In these wild patches, juts of trunk and branch and the sun shards they shape make art above scribbles of bushes and cross-hatched grasses. It has rich and varied form. This is what the forest desires for itself. Another valley over, a bloated lake sprawls in a posture of surrender. Its shoreline is tense as a fist: it is not fringed with the customary clustering flora that embroider the edges of free water, but is ringed by a gravelly orange collar of bare ground. The lake is not itself. It is one of many rivers in Tasmania that are locked up behind dams and swollen like gaseous corpses for the state’s gargantuan hydro-electric installations. A battery-caged river being fed into a machine to make electricity.

At the edge of plantations, though, trees break out from the order imposed on their neighbours and kin. Their branches jut and crook in the light and wind. They throw out blossoms in non-compliance. A river, too, might protest its capture by overtopping the dam, by brewing poisonous blue-green algae or withholding silty nutrients behind the detested wall.

These gestures of rebellion are an invitation.

The contrast has roots in Europe in the seventeenth century, when the scientific revolution was the scene of a dispute between vitalists and mechanists. At stake was the location of agency and meaning-making. For vitalists, the whole world is animated by free will. It teems with vivid self-generating and self-governing genius at all scales. For mechanists, these qualities – intention, agency – reside solely in the mind of the human subject. This mind, the self, surveys and oversees a world whose motion is mindlessly mechanical. Stuff bumps dispiritedly into other stuff. Forces act upon objects and their actions are regular and predictable as clockwork, since matter itself is inert. The dualism of subject and object, mind and matter, drained the world of vitality. Out of this belief system, a scientific tradition was inaugurated that is surprised over and over to rediscover the selfhood, feelings and personalities of other creatures, or the mysteriously wilful properties of the smallest particles. Out of this belief system, too, a habit of domination became entrenched, and it has brought the living systems of the Earth and its human societies into turmoil and peril. The characterisation of the world as machinery enables that domination, since machines require masters. Francis Bacon declared the sphere of knowledge inseparable from the field of power and infamously promised that he would bring nature to his people “in chains.” Nature was to be subdued and dominated, a process that became irreversible in the following century with the invention of the steam engine and the onset of the machine age.

In the mid-1940’s, Karl Polanyi reviewed the cataclysmic consequences of market economics and saw that industrial machines had wholly reorganised the societies that built them by establishing the conditions for the subsumption of those societies by markets. The physical qualities of industrial machines demanded this. For machinery, outputs must be regular, defects discarded and the pace unrelenting. The labour and materials that go into machine production must be available to be purchased on demand and rendered exchangeable. In other words, nature and its people had to be made into commodities. Other values and relationships must be stripped away for such exchange to work:

Machine production in a commercial society involves, in effect, no less a transformation than that of the natural and human substance of society into commodities. The conclusion, though weird, is inevitable; nothing less will serve the purpose: obviously the dislocation caused by such devices must disjoint man’s relationships and threatens his natural habitat with annihilation. (Karl Polanyi, The Great Transformation)

Eighty years on, the reach of machine-culture is almost total. Societies and ecosystems all over the planet have been reorganised around its peculiar demands. Even people, according to Richard Dawkins for example, are imagined as remotely-controlled engines. Our genes, in this view, behave precisely as the imaginary “rational actors” of economic models are mythologised to behave – wholly selfishly towards their purpose, which is mere survival. This is not how nature works, but it does resemble machinery.

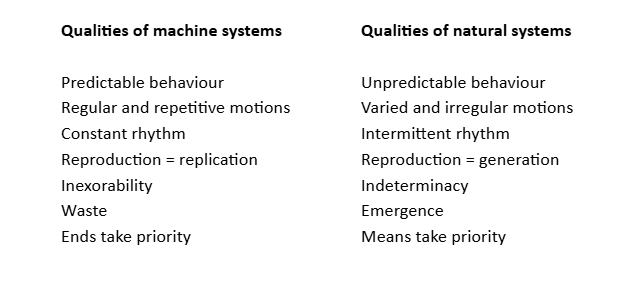

In the metaphors adopted by the mechanists, it is striking how the machine embodies and propagates qualities that are the inverse of natural systems at all scales. This is the contrast made visible in Tasmania’s landscape:

A people whose society has reshaped itself in the likeness of machines could well end up destroying the basis of their own livelihoods because they come to conceive the mechanisms of their society as inexorable, too, and operating beyond their control. There are implications of all of this for how we conceive politics and governance. A rational actor in such a system is not a being in right relation to the world around it, but an isolated entity in lonely pursuit of gain at others’ expense. The range of possible responses to coming perils are severely constrained by metaphors shaped by machines and domination. In a breathtaking inversion, this ideology projects unthinking selfishness onto an mythologised state of nature while an imaginary “free” market economy cloaks itself metaphorically in the self-governing creativity of natural systems. Even judgement is being ceded to machines: software programs are given the tasks of comprehension, design, communication and story-telling. Questions about what to do next are fed into economic models and if the computer says “no,” it is decisive. Confidence in our natural selves and our capacity to create and renew our society turns on emancipation from this paradigm.

Machine culture has a particular hold on Australia because the modern nation that goes by that name began to be colonised just as the Industrial Revolution got underway. Watt’s steam engine was patented in 1769 and two decades later the cataclysmic consequences of the machine culture were brought to Australia and began to annihilate its First Nations’ nature-cultures. In contemporary Australia, the unsettling double-face of “the environment” makes another illuminating contrast. One aspect is decorative and in need of saving by clever modernity, the other is implacable, barbaric, and threatens to tear that modernity to pieces. In Australian politics, “the environment” is patronised as an indulgence: in times of prosperity, or for light relief, we can afford to have it on the national agenda. As a political portfolio, environment tends to be seen as “soft.” It is not part of the apparatus of real power (and it is always power that matters most, not beauty, liberty or love). Being photographed with a marsupial, an environment minister may soften the image of a government that otherwise reduces people and nature to exchangeable economic units, but such matters are not treated as serious in the way that the work of maintaining the machine called economy is serious.

The other face of the environment, however, is deadly serious. When it is in the path of the economy, nature in Australia becomes a world-ending threat to prosperity and Australia’s way of life. This is when the environment’s cuteness becomes a monstrous absurdity. This aspect is on display in headlines about a sea snake “threatening” a multi-billion-dollar gas development by dwelling unwittingly on a remote coral reef where its kin and culture have lived freely for half a million years and where a wealthy corporation now wants to build an LNG facility. The way the Australian mining industry characterises modest efforts to improve national environment law gives expression to a deep anxiety about the unfitness of Australia’s machine society for the world it inhabits. It betrays apprehension about the coming reckoning.

To read feeling, will, and meaning into the world around us against dominating culture has been given the taboo term “anthropomorphism.” If the human mind is the sole possessor of agency, any recognition of agency in the world beyond it must be deemed false, even dangerous. This is the legacy of mechanism. On the contrary, it is anthropocentric to consider these qualities exclusively human. The forest and the river in Tasmania and the sea snake on Scott’s Reef want only the commonest desire – the freedom to be themselves.

In their expression of that desire, they are offering us an invitation.

What is the nature of the invitation? Let’s read it.

A tannin-stained creek dribbles over sand towards the sea. Its body braids itself, forming scalloped plaits of water that cross each other and reflect the colours of the sky and foliage above and around it. It makes patterns like chevrons, one of the oldest shapes in human art, and as time passes the patterns alter and renew.

“Come to me, said the world…”

At the river mouth, light glances on water and moves through it, scribbling wobbling oblongs onto the sand. The irregular pulse of swell is both shaping and yielding to the entities around it. Sand mounds below in more waved lines. Fish bob. Kelp heaps to and fro in sleek ribbon-scrawl. Each detail is an invitation and an answer. This is how Louise Glück hears it, in “October;”

Come to me, said the world.

This is not to say

it spoke in exact sentences

but that I perceived beauty in this manner.

Sunrise. A film of moisture

on each living thing. Pools of cold light

formed in the gutters.

“With our senses applied to the surrounding world,” wrote Thoreau, “we are reading our own physical and corresponding moral revolution.” The experience of beauty invites us to connect and through connection to ourselves become free to be beautiful and invite further connection. We are offered the means to come out of lonely isolation in a mechanical world, to participate and change, to touch and be touched by the film of moisture on each living thing. Water is a marvellous courier of this invitation and its answer because it so relishes running together, changing form and reciprocating. Touch the film of moisture, and it will cling to your fingertip. The waste and wreck of all this beauty is not inexorable. That’s the machines talking. All around us now, there are processes unfolding – global heating, changing relationships, breakdown of old systems and emergence of new ones – that are indeterminate and contingent, like everything else real in the world.

We are not only reading the world, but writing it, and making art, making society as part of it. “Represent me, says the day,” in Jorie Graham’s poem “In reality.” Representation here means art, but it implies politics. How can an irreducibly complex and continuous world be represented? Economic models cannot do it, but art might, because it exhibits the qualities of natural systems, not machines. In Emily Kam Kngwarray’s “After rain,” the artist’s fingertips made and keep making dots of many colours – dark and pale green, golden yellow, coral pink. A turning season and the arrival of new growth is happening as we stand before the canvas. There is pattern, but the pattern is not predictable. The dots run together and form trails. Shapes emerge. Every dot, every pencil yam leaf, every minute of witness to the painting itself is distinctive, and each cannot be itself without its relationships to each other and all others. In a video and story accompanying the Emily Kam Kngwarray exhibition at the National Gallery of Australia in 2024, Jedda Kngwarray Purvis and Josie Petyarr Kunoth tell us, of Kngwarray’s art:

“If you close your eyes and imagine the paintings in your mind's eye, you will see them transform. They are real-- what Kngwarray painted is alive and true. The paintings are dynamic and keep on changing, and you can see how realistic they are. You might wonder, ‘Hey, how come these paintings are changing form?’ That powerful Country changes colour, just like the paintings do. The Country transforms itself, and those paintings do as well. That’s why the old woman is famous.”

Country transforms itself and the painting likewise. It vibrates in the eye and body of the witness so that we, too, are reading the artist reading the land and changing. Sovereign genius is strewn in the land and the artwork and gathers itself into complex order. It wants to express itself and can do so only through connection, right relation. Emily Kam Kngwarray is justly famous as a co-creator in this process, but every part of our lives is involved in it, including politics.

Natural systems have relations, laws, cultures and other means of enabling free expression and negotiating competing claims. The freedom of the wild doesn’t mean absence of conflict, but offers the means of creating through that conflict and in the reciprocal acts of creation at the shoreline, or among the painted pencil yams. When people dump pollution in rivers, push over habitat for mines, and alter the atmospheric conditions that create and maintain the Earth’s stable climate, they impinge on sovereign realms, but the habit of domination obscures this truth.

One of the side effects of wielding power is the diminished imaginative faculties of the power holder: for those who can impose their will without consent, seeing and understanding other people and the world around them ceases to be a precondition for their actions being effective. Caution is warranted. The renewal of experience that comes with cautious attention generates a wholly different political sensibility. Interactions with other nature-cultures becomes a kind of diplomacy – the establishment of trading and thoroughfare relationships with a neighbouring ecology with whom one does not share law, language or custom. To take resources from or spread wastes into any territory, we would first have to make representations, agree terms and attempt to understand the desires, needs and boundaries of that territory. We would need to reciprocate.

In the real world of forest, estuary, seashore, every aspect of life is a negotiation of this kind. A river does not take the shortest course to the sea. The properties of water and the tug of gravity draw a river seawards, but on its way, it negotiates topography. It picks up and deposits minerals and other nutrients. It gives and receives groundwater from its bedrock. It receives runoff and gives back to the floodplain. It sinuates. Barriers like fallen logs are good for it, because they slow the river down and spread its power. A river that runs too fast, like a fast-tracked decision or unchecked executive power, does damage to itself and others. The power of a river is moderated by the processes of the landscape and, reciprocally, those who live with the river – trees, boulders, fish – attend to and respect its ways. Waterways are a model for how to navigate conflicts, make decisions and get anything done in a society that wants to last longer than a machine. Take other entities seriously, slow down to negotiate obstacles, establish right relations. In like manner, political, social and corporate power needs to be moderated by processes that invite the public to participate directly and allow for emergence and creativity. Every decision can be a kind of art-making if we bring machines into the service of life, and not the other way around.

In the technology of administration, the difference between organic process and machine-like procedure is as stark as the difference between wild forests and plantations. Australia has elaborate procedures for securing approval from governments to do harm to the natural world. This is “green tape” and it is generally more of a procedure than a process since participants largely know from the outset how it will conclude. The underlying structure of domination is thereby revealed: the people participating are doing so on terms made by the machine’s master. The mechanism is in motion and none of the operating pieces may alter the script. Accordingly, while the outcome of a process is indeterminate, the result of a procedure is largely predictable. In the alternative, when all of us are free, including living things and the myriad land- sky- and sea-forms, life is sympoiesis. Art, nature and society are expressions of selfhood in relationship, and in politics this is embodied in the spirit of direct action – the political expression of the rebellious river overtopping its dam. Whether people are standing in front of bulldozers, withdrawing their labour, taking control of a public meeting or guerilla-gardening, direct action involves an assertion of what Murray Bookchin described as “The right of people to assume unmediated control over public life.” Direct action is an affirmation by ordinary people of their capacity, competence and agency in the ecosystem of public affairs. It doesn’t have to be illegal, nor is it necessarily protest. “Assuming unmediated control over public life” is a good description of the three year process by which the northern rivers of New South Wales was declared gasfield free by the community over three years, a collective decision which the state government subsequently formalised. Like a river, direct action slows down consequences and opens possibilities. Like art, it honours the irreducible complexity of people and their inter-relations with the world and each other. Every fingerprint is a different colour. Society is a creative process. In contrast, machine-made decisions have all the qualities machines bring to society: sameness, inexorability, wastage and the impersonality that absolves its users of responsibility for its consequences.

Ten years after Watt’s steam engine was patented, the mythic young weaver Ned Ludd first smashed a textile machine in Manchester. Ever since machine-culture started rending social and natural relations in its sausage factory, the free field agents of art, nature and politics have been throwing spanners, algal blooms and pots of paint into the gears. In truth, the machine cannot carry on this way. Its qualities are out of keeping with the world around it and so it is under immense tension. It needs fuel and constant maintenance or it will break down. Breaking things down and making new forms from them is what nature does, what we do, what water does. Water soaks, seeps and corrodes, climbing walls, condensing into droplets from thin air and falling in merciful downpours onto hard soil with the pungent smell of new possibility. While it would be rash to presume to precisely read and express back the desires, invitations, gestures emanating from each shape, scent and sound of the wild, it is far more damnable to remain insensible to them. Any faithful answer will cultivate qualities like emergence and agency, qualities that bring the seeming inevitability of environmental collapse back into uncertainty.

Let representations be troubling in their ambiguity.

Let the outcomes be unclear for a time, while means take precedence over ends.

Let expression and creation be purposeless, like the marks where fingers touch and the articulations of shadow as light passes through a tree canopy.

The personal, artistic and social challenge is to interrupt the inexorable whirring metronome in our own minds that says, “There is no way to change this; you are alone.” That is the machine talking.